January 2024

Physical, Mental or Financial Health?

The Impossible Tradeoff of U.S. Healthcare – A Qualitative Analysis

Introduction and Method

Undue Medical Debt (RIP) and Neighborhood Trust Financial Partners (Neighborhood Trust) conducted a series of in-depth interviews with people who volunteered to share their experiences with medical debt and the health care system. Undue focused our interviews on five debt abolishment beneficiaries from the southern United States; three of our participants identify as Black women, two participants identify as having a disability, and all five participants were employed and had insurance at the time their medical debt was accrued. Additionally, all five participants had an income at or below 400% of the federal poverty level (FPL)—or roughly $124,000/year for a family of three. Each interview was conducted via telephone and lasted about an hour. Participants were asked a series of questions designed to explore their experiences of navigating the health care system, with a particular focus on pain points with insurance, access to care, and billing. We then analyzed interview transcripts for overarching themes, which were input into a qualitative data analysis software called MAXQDA for further analysis. We are deeply grateful to our participants for their willingness to share their stories, and hope this brief helps continue a productive conversation around eliminating medical debt and improving access to care.

These invaluable interviews reaffirmed the survey findings covered in our previous briefs—insurance is not enough, and medical debt (whether experienced or anticipated) has a negative impact on people’s mental, physical, and financial health. This brief focuses primarily on the patient experience and potential solutions for hospitals and providers, for more insight into the employer and employee experience, check out Neighborhood Trust’s companion brief.

The Stories Behind the Themes

All five of our interview participants provided important insights into the patient experience of navigating medical debt. Some of them shared a visual to accompany their story. We provide a summary of their stories below:

Interviewee #1 – Lucinda

Debt Abolished: $1,767.84 between December 2022 and September 2023

Current Employment Status: Employed

Lucinda lives in North Carolina and is the widow of a recipient of our debt relief program. Her late husband Tony underwent multiple medical procedures towards the end of his life, including rotator cuff surgery, hospitalization for pneumonia, care related to prostate issues, and carpal tunnel surgery. Tony was insured through Lucinda’s employer-provided plan, and it wasn’t until after he passed that she learned he had been struggling to keep up with his medical expenses. Lucinda describes paying what little that she can toward any medical bill—including some of Tony’s—to avoid dealing with collections. She is a ‘responsible patient’: she tries her best to pay off her medical debt, putting whatever she can towards it each month.

Interviewee #2 – Simona

Debt Abolished: $486 in November 2022

Current Employment Status: Full-time $15/hour

Simona accrued the debt abolished by Undue after being hospitalized for type 2 diabetes. She’s worked as a nursing assistant in Georgia for more than 20 years and loves the job; in all this time, despite her years of committed service, she has yet to receive a raise. Money is tight for Simona—because she cannot afford the monthly expense of $200 for insulin, she rations her medication, leading to more complications with diabetes. A responsible patient: she wanted to pay her medical debts but couldn’t.

Interviewee #3 – Patrick

Debt Abolished: $232.84 in December 2022

Current Employment Status: Full-time $44k/year

Patrick lives in Tennessee and broke two vertebrae during a home repair accident. After falling off a ladder, he was taken by ambulance to the hospital where he received a CAT scan, was put in a back brace, and spent one night in the emergency room. The debt abolished by Undue was from a later visit to a physical therapist; Patrick assumed his co-pay would be between $30-50 but instead received a bill for $250. Because this large out-of-pocket expense would be recurring, he opted not to go to physical therapy. The ‘defeated patient’: Patrick described feeling hopeless and deflated to the point where it didn’t matter if he paid for treatment or not.

Interviewee #4 – Gina

Debt Abolished: $250 in January 2021

Current Employment Status: Unemployed since August 2020, recently approved for disability

Gina lives in Texas and was diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, in 2020 and requires ongoing care. Her chronic illness is a full-time job, requiring her to manage daily symptoms like shortness of breath as well as maintain an oxygen tank she uses 24/7. Gina was employed full-time, but the severity of her COPD forced her to leave her job; a few days before our interview she was finally approved for disability benefits after three years of waiting. She described feeling stressed about her treatment and medical debt—her out-of-pocket costs for oxygen alone are $200/month and she had to give up other interventions that significantly improved her quality of life. The patient with chronic illness: Her time and energy are spent managing her illness and the day-to-day logistics of being a person with a disability.

Interviewee #5 – Christine

Debt Abolished: $735 in December 2022

Current Employment Status: Full-time $65k/year

Christine is a schoolteacher and mother in Mississippi. She incurred her debt after falling and breaking her finger. Christine is insured through her employer but describes the insurance as being useless. She is deeply afraid of accruing more medical debt and avoids going to the doctor “even if it could be something big.” The stress of contending with medical debt while caring for her family and maintaining a full-time job is palpable in her interview. The responsible and defeated patient: she pays what she can on her medical debts and is terrified of accruing more debt. This fear prevents her from fully taking care of her health.

Key Themes

Our interview participants provided incredible insight into their lived experience with medical debt and navigating the health care system. For the purposes of this brief, we focus on the most unifying themes: insurance is not enough, navigating medical billing leaves some patients feeling disempowered and untrusting of the wider system, and the impact of these shortfalls on people’s mental health.

Finding: Insurance is not enough—for too many, it is an investment with few benefits.

Health insurance coverage can be a source of confusion for participants. In theory, buying health insurance coverage should provide financial protection, but in practice too often it does the opposite. Our participants described insurance as being expensive, impossible to predict, and often acting as a barrier to accessing needed care. They described feeling further burdened by their insurance, which runs counter to how insurance should work. The traditional message that if you pay for health insurance coverage you will be protected from unaffordable out-of-pocket costs is often far from certain, especially for the financially burdened population Undue serves. Doing everything right (paying for insurance) and still finding yourself in a financially precarious situation is disempowering—a sentiment that was a leading pain point for our participants.

“I am a diabetic and frequently throughout the year I incur medical debt with that. Just routine visits for medications. My thing is, if the insurance—and I know all about the politics behind insurance—but if the insurance would cover more or do more towards medical debt, it would be a big burden relieved, you know? If I do have to be admitted into the hospital, let’s say, and the visit is 10 grand, why am I still responsible with monthly insurance payment? Why am I still responsible for six grand? Wasn’t the insurance, you know, doing more to satisfy the debt, helping to bring it down? That would really be a relief.”

Simona

All participants echoed Simona’s sentiments regarding insurance. They described feeling that there are little to no benefits to paying monthly premiums for their employer-sponsored health insurance plans. The process of securing health insurance coverage can be categorized as “doing the right thing” because the universal understanding (conveyed by our participants) is that coverage is necessary to make medical expenses manageable. This misconception, for individuals who lack affordable/comprehensive insurance, then causes participants to feel frustrated and duped, because they cannot afford the out-of-pocket costs and incur medical debt. Participants of this study are underinsured, meaning their insurance is inadequate and unaffordable.

All participants understood that out-of-pocket expenses are to be expected; they had no problem with paying reasonable co-pays but struggled with other unexpected costs. Patrick spoke of this feeling, saying “—you know, it feels like I’m already spending enough money just to have insurance and I know that no matter what, if I go to the doctor, insurance isn’t going to cover 100%. The only thing I know that my insurance covers 100%: I get blood tests once a year.” Beyond monthly premiums and deductibles, participants described their co-pays and out-of-pocket expenses alike as unpredictable and unaffordable. Whether it was a hospital visit, procedure, or treatment, everyone felt unable to predict what their medical expenses would be. Participants described day-to-day bills such as those associated with electricity, mortgages, childcare, and other necessities, as competing with their ability to afford medical bills.

The shortcomings of insurance are especially clear when looking at the experiences of our participants with chronic health concerns. The false promise of affordability combined with the need for ongoing care means your health care expenses can quickly become untenable—especially with growing deductibles and shifting health insurance coverage. Our participants with chronic health concerns described living in a world where they know there will be regular costs, but they’re never sure just how much. When combined with the exigencies of daily life, things become incredibly stressful. Christine shared how “[w]e were struggling financially…so to have to pay $65 to $75—well, it can really be anywhere from $25 to $65, depending on where you go…[i]t was very difficult for us, like we were really dealing with a lot of debt.”

Regardless of insurance, health care is unaffordable for people, especially those with ongoing health care needs. For example, Gina has been living with COPD since 2020, requires 24/7 oxygen therapy and has been without insurance coverage since November of 2023. Like Gina, the treatment that Simona requires is lifesaving and therefore required. “Like one of my medications is a big out-of-pocket: the insulin, I can’t afford that insulin every month, so I have to kind of cut back on it just so I could save to be able to get it the following month if that makes any sense to you. That’s how I must live. $200 for insulin a month, it’s just not feasible for me,” she says. This financial and physical sacrifice puts her health at extreme risk. The fear of accruing more medical debt and facing extraordinary collection actions (e.g., wage garnishment, damage to credit scores, and being taken to court) lead participants to do things like ration insulin and defer care. A single interaction with medical debt can lead participants to undertake the drastic and harmful action of delaying care and/or ignoring symptoms entirely to avoid medical bills they know they won’t be able to afford.

An additional pain point for insured patients is caused by the referral process. Referrals can serve as barriers that further delay care and allow for health and financial conditions to worsen. The referral allows access to a specialist or test that participants need to (1) get a diagnosis or (2) monitor the trajectory of their illness and treatment. Participants described scheduling appointments as a barrier to accessing health care also. For Simona, this is the biggest pain point she feels when navigating the health care system, “…wait on an appointment. Like if I need to go see the eye doctor, I can’t see the eye doctor for four or five months down the line.”

Payment plans, like insurance coverage, are presented as solutions to the issue of unaffordable health care making it difficult to question or criticize. For participants, payment plans were the only option they were provided at the time they received care for the debt erased by Undue Medical Debt—no one was provided information on financial assistance policies. Along with payment plans, participants described being told that they had 60-90 days during which they could come up with the money or enroll in a plan. This timeframe creates the unrealistic expectation that people can figure out how to afford insurmountable medical expenses, causing stress and anxiety for patients.

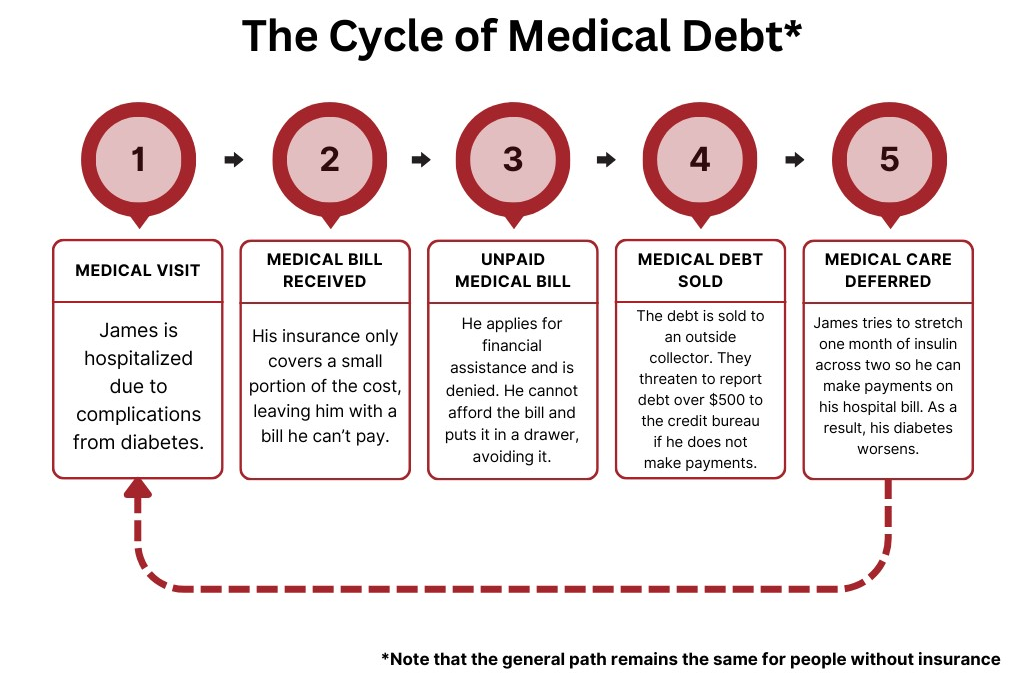

Finding 2a: The way we bill and pay for health care leaves too many people trapped in a cycle of medical debt. High health care costs, inflexible or inconsistent financial assistance policies, and skimpy insurance coverage combine to create a cycle that drives patients (particularly those with chronic illness) to become sicker and financially vulnerable. Simona stretched her insulin across two months and Gina returned durable medical equipment because they could not afford their monthly payments. Forgoing insulin and losing access to a ventilator both greatly decreases quality of life and significantly increases risk of poorer health outcomes. Simona and Gina were faced with a false choice—physical or financial health?—that led them to become trapped in the cycle of medical debt. This is illustrated in the figure below:

Figure 1.

While common, this cycle is not a universal experience. When financial assistance policies are accessible and easily applied, hospitals are able to help prevent patients from falling into this difficult cycle.

Finding 2b: The experience of billing is confusing and difficult, leading to an erosion of patient trust in the wider health care system—and leaving them feeling as if “the whole thing is broken.” Billing is a tremendous pain point for people navigating health care. Our participants shared how uncertainty over the cost of care, confusion over payment options, and near constant pursuit for unpayable bills all combined to create an emotionally difficult and traumatic experience. It was striking how they often used language describing feeling abandoned and unseen by a system they view as “prioritizing profits over patients.” As one person stated, “I don’t know that anyone cared about my health, it was more about financial gain.” They describe trying to navigate a confusing, often adversarial system that punishes them for not being able to afford their bills or understanding the intricacies of insurance, medical billing, and reimbursement.

All our participants (save for Patrick, who felt defeated by the health care system) continued to try and pay down their medical debt—but even these efforts sometimes went awry. Lucinda described one experience from last year, “…I had been paying on it every two weeks and I thought they were putting the bill towards both sides, the physician side of the bill and the hospital side and come to find out they were only putting money on the hospital side. So, I got a letter saying that I was going to be turned into collections on the physician side being charged the whole amount.” Billing can be extremely confusing, especially for a layperson, and the opacity of the process sometimes leads to people accruing more debt even when they are actively paying their bills.

Indeed, the administrative burden that comes with navigating billing and payment as a patient requires the help of a navigator. Information on financial assistance programs and policies should be shared as soon as possible, but none of our participants could recall being told about options by their treating hospital or provider; instead, they heard through word of mouth or assumed they would not qualify and therefore didn’t apply. When people did apply, they were denied or received partial assistance. The explanations for denials were confusing, inconsistent, or non-existent (to quote Simona, “I received a letter saying that I was denied for that program due to my income which of course I didn’t understand that.” She makes $16 an hour.) For many patients, financial assistance policies begin to feel like secret knowledge you have to fight to obtain.

“It’s sometimes upsetting to me because you’re trying to do what you can, but they’re not accepting of that and like I said, you have what I consider my major bills: my house payment, my electricity, my water, you know, things of that nature that you don’t want to fall behind on and you got to maintain. But you got somebody, a collector, coming at you saying, ‘well, we need our money too.’ You know, it’s understandable but if you’re not willing to accept what I can give, then what do I do?”

Simona

When financial assistance is difficult to access, payment plans become more important. On balance, patients do their best to try and make their monthly payments if conditions allow—often at the expense of their health (e.g., trying to stretch insulin over several months or skipping it altogether). Payment plans can be helpful when they are created with rather than for the patient; when they are not tailored to individual financial circumstances, they fail to address the root cause. As aptly put by Simona, “if I don’t have $60 today, I won’t have $60 tomorrow.” While patients make difficult tradeoffs to access and afford care, our interview participants did not perceive their health care systems as making similar sacrifices—instead, they describe feeling subsumed by a system that is inflexibly focused on profits. Things like billing errors, high pressure to make unaffordable payments, and a confusing morass of billing procedures (often with the insurance company saying one thing, the billing department another, and the patient caught in the middle) make it very difficult for patients and providers to maintain trust.

Finding 3: The specter of medical debt, whether imagined or experienced, has a significant impact on people’s mental health and likely overall health outcomes. The emotional toll of medical debt is a throughline in our interviews—the intricacies and shortcomings of insurance coverage and the amount of work required to understand medical billing create a tremendous amount of both administrative and emotional burden for people. The confusion can result in mental health struggles for patients; multiple participants spoke of feeling like the system is “designed to confuse and frighten you,” keeping people anxious and unsure in a moment that may already be difficult. This sense of confusion can lead to feelings of depression—as Patrick said, “I feel overwhelmed, I feel like, why try?” Receiving a medical bill is marked by a strong sense of despair for all our participants; they describe feeling hopeless when going up against what they experience as a system that does not view them as an individual. Too often, people try and cope with this despair either with a false sense of bravado or with total denial— “I knew I couldn’t pay it, so I put it in a drawer and forgot about it.”

The stress of navigating the health care system and avoiding medical debt extends its tendrils throughout all aspects of people’s lives—they make difficult tradeoffs from the type of food they buy to how much medication they use to save money to access care. This is particularly true for people with disabilities and chronic illness; many participants shared stories of making do with inferior treatment to try and save money to put towards existing medical debt, resulting in a population interfacing with the health care system that is best described as resilient but exhausted.

[It’s about] not being able to really just live a peaceful life. Not knowing who is coming at you next. So, it’s a lot. It’s a lot for me. Especially when it comes to medical debts, because like I said earlier, I feel like insurance is a joke. And I pay all this money out monthly for insurance and still have medical debt behind it and it can be very stressful because like I said, you got to be able to maintain a decent life with the medical debt that I have.”

Simona

The fear of medical debt takes up mental bandwidth that could be used elsewhere. Each person we interviewed shared how their fear of medical debt makes them pause before going to the doctor—or drives them to completely avoid it, even when they know they need it—causing them more worry about their health and perpetuating the cycle of illness and anxiety.

Participants who had bills sent to collections shared insight into the difficulty of the experience—they describe receiving 3-4 calls a day, people calling until their voicemail box was full, demanding payments they didn’t have. Christine described the entire experience navigating the health care system as “depressing…embarrassing…[and] traumatic.” Like many people, she now defers necessary care to try and save money and avoid future medical debt, knowing she is potentially ignoring something serious and risking higher costs in the future. She noted, “people are walking around [like] ticking time bombs. Like, they’re literally dying and they just…avoid the hospital because they can’t afford it.”

Proposed Solutions

There are changes to be made at every level of the health care system—from insurance companies to employers to medical staff—but for the purposes of this research we focused primarily on hospitals and other providers who serve as a critical first point of contact. The proposed solutions below outline steps they can take to ease the burden of medical debt for the patients they serve.

Increase Provider Trust: Relieve administrative burdens for patients. For participants, navigating the U.S. health care system is burdensome. Accessing medical care requires time and capacity, both mental and physical. Fulfilling a myriad of administrative tasks is a focal point of this process. Researchers define administrative burdens as (1) learning costs; the process of gaining access to services or benefits like health insurance plans and financial assistance, (2) compliance costs; the process of compiling and completing required documentation necessary for access to, as described by participants, health insurance coverage, financial assistance, tracking progress on medical payments made, complying with referrals and scheduling appointments, and (3) psychological costs; the emotions, such as stress or frustration felt by participants as they navigated these processes. Hospitals should consider:

- Increasing accessibility of their financial assistance program to mitigate financial struggles related to health care;

- Simplify financial assistance forms and use no-touch solutions like presumptive eligibility;

- Research hours patients spend navigating referrals and scheduling to measure potential delays in care;

- Provide patients access to financial counselors, navigators and other ‘expert’ support both within the hospital and in the community to support their patient journey through bilateral communication and direct feedback;

- Educate all frontline providers about the fears and burdens of medical debt to create an environment that can reduce stress and stigma.

Hospitals and other providers should build on best practices and reexamine billing & financial assistance policies to ensure they meet the needs of the patients they serve. Person-centered care remains the gold standard in health care, and a key component of remaining person-centered is building and maintaining patient trust. Difficulties in accessing and understanding both billing and financial assistance policies threaten to erode that trust; hospitals and other providers should consider identifying new approaches to the patient-biller relationship. These approaches could include trauma-informed care (an emerging strategy in health care), as well as screening techniques like presumptive eligibility for financial assistance. Providers could also consider adopting a “no wrong door” policy for financial assistance; patients should be presumptively screened for eligibility AND applications should be able to be routed through any staff person.

Providing community care and building patient trust while maintaining margins requires support from beyond providers. The majority of U.S. hospitals are nonprofit and will require support from state and federal governments to better assess patient financial standings and make true accessibility a reality.

Continue research into the mental health impact of medical debt. This research should be used to inform staff training. While it is generally accepted that medical debt has an impact on mental health, research is in its nascent stages. We need more research to help clarify how medical debt and navigating the health care system (including insurance plan design) impacts people’s mental health and how we can protect against these effects. Early work seems to indicate that taking a trauma-informed approach can improve outcomes and decrease costs and should be explored further within the specific context of medical debt and billing.

Hospitals should consider making sure providers and other staff (including billing staff) are aware of the impact of medical debt on mental health. Billing staff may have to contend with phone calls and emails from patients experiencing distress; providing them with person-centered de-escalation training and resources they can give to patients may help diffuse difficult situations for both patients and staff. These resources could include warm hand-offs to social workers, a crisis line phone number, and financial support. Finally, hospitals should consider leveraging the insights of existing patient and family advisory councils (as well as staff) to determine the most appropriate and useful resources for their patients.

Call to Action: Insights and Solutions from People with Medical Debt

Real policy change is grounded in the insights and experiences of the people most directly impacted. At the end of each of our interviews we asked participants to share their “magic wand” answers—if you could change one thing about the health care system to make it better, what would you do? All five of our participants called for affordable, accessible healthcare for everyone in America. Our interview participants were concerned with making sure everyone can access care when and where they need it, without fear of going into medical debt. A selection of their answers is provided below:

- I understand that insurance has to be paid, insurance has to charge, and doctors charge…but it’s like sometimes they do useless stuff. I’d like to be able to skip to the end, instead of doing x-rays, CTs, MRIs, why not cut out those extra expenses if we know what the best choice is going to be? Why spend the extra money? Instead of the patient having to spend the money for it. — Lucinda

- I would make it where everybody received free health care. You know, but I would make it where the doctors and nurses and everybody involved in their treatment still receive some type of compensation. — Simona

- I would get rid of insurance companies and we’d have to figure something else out. A single-payer healthcare system like Canada or something I think would be ideal, but I don’t pretend to know anything more than that. I just know that other people have figured it out and here we are. — Patrick

- I would look at healthcare just being overall more affordable, whether you can afford it or not. I think some of the costs of things that they provide are outrageous. And we do understand that equipment costs and costs to have people manage departments and run the equipment, but some of the things I think are just overinflated and really need to be reconsidered. But whether you have the insurance or not, I would look at hopefully making healthcare more affordable, when even if you don’t have insurance you can still get the care you need. — Gina

- I would turn us into Canada Jr. I feel like our government in the United States is more than capable of giving health care to the citizens of the United States. — Christine

Conclusion

The information and knowledge imparted by participants was done so with the understanding that their experiences and insights regarding the health care system and medical debt will directly inform the solutions we developed. As part of Action Research (AR), this inquiry was oriented towards taking specific actions vis-a-vis health care policy.

Project Background

Undue Medical Debt and Neighborhood Trust are partnering to generate awareness, understanding, and solutions that empower employers and hospitals to do their part to reduce medical debt. This work is designed to amplify the voices of low-wage workers and gain their insight into medical debt and health benefit designs. Phase 1 of this project entailed surveying 230 people about their experiences with medical debt, which you can explore in our previously published briefs.

This brief represents Phase 2 of the project; between our two agencies we conducted 10 qualitative interviews with low-to moderate-income volunteers. The average annual income was $46,000, 7 participants identified as Black or African American, 1 as two or more races, and 2 participants as white. 9 out of 10 participants have insurance through their employer, and the 10th was recently approved for disability benefits. The total geographic reach of the project is scattered across the country, with participants from Texas, New York, Maryland, Georgia, Tennessee, South Carolina, and Mississippi. Each interview lasted about an hour, and participants received a $50 gift card for their time. Our organization analyzed five interviews, with two coders each to ensure inter-coder reliability and account for biases. Finally, we consolidated findings before separately identifying and labeling the top themes to emerge from each interview.

Written by: Camila Salvagno and Lindsey Zischkale